Aylin Basaran

(c) Soren Kloch

Aylin Basaran

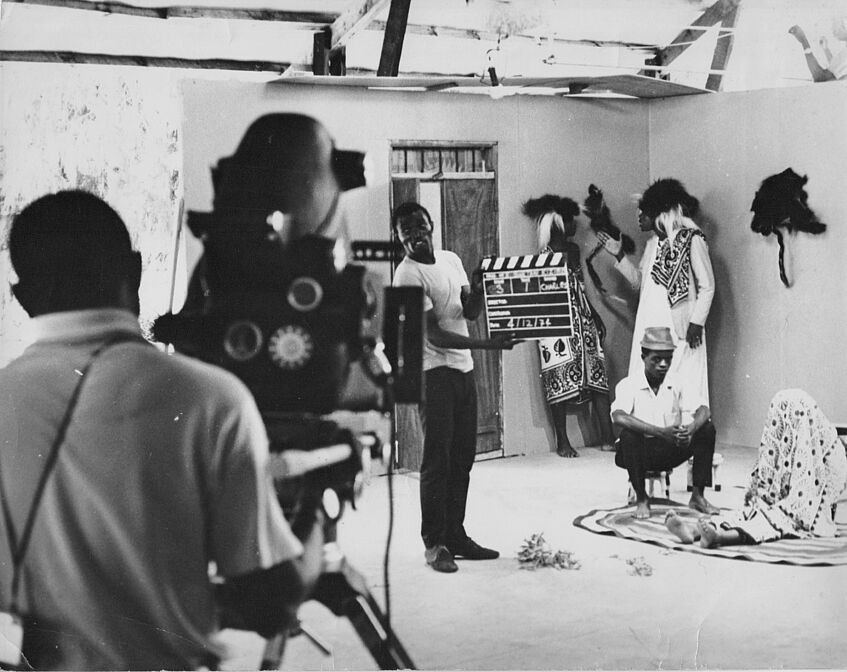

"Sinema Ujamaa" – Film Production in Independent Tanzania.

Appropriations of the Moving Image in the Postcolonial Context of Nation Building, African Socialism and Memory

The global rise and spread of the moving image coincide with the heyday of colonial domination. Film hence became a cultural tool of colonial indoctrination on the one hand, and a means of liberation for the colonized on the other. While the interdependence of industrialization and the rise of the moving image in the ‘western’ world has been widely studied, little research has been conducted on the specific interplay of decolonization and audiovisual technologies, focusing on both structural phenomena and national particularities. Studying the appropriation of film in postcolonial Tanzania, I apply a notion of technology informed by postcolonial interventions in science and technology studies which see innovation not merely in the act of continuously creating new apparatuses (and thus creating new necessities), but in the creative appropriation of gadgets, practices, and aesthetics in the pursue to satisfy the particular socio-cultural needs and desires of a given society and time. The decolonization of the moving image encompassed both, a struggle for access and a struggle for visual self-representation. At the time when colonized territories became independent, audiovisual media played a great role in nation building. However, they were still suspicious of perpetuating the legacy of deprecative colonial representation and of creating capitalist desires rooted in western culture. This was particularly the case in countries which, like Tanzania, opted to pursue a socialist path.

Soon after independence, officials proclaimed the need to establish a national film industry in Tanzania, in order to create an independent imagery of the young nation. However, controversies arose both over the kind of films as well as the types of institutions most suitable to reach this goal. The vision of film ranged between an advanced information medium, an asset of educational campaigns, a way to promote the development and ideals of the nation, a new form of art and critique, or simply entertainment for the masses. Conflicting visions were promoted by various ministries, the government, the TANU party and active film makers as well as by external donor institutions. Despite efforts to centralize film production, this resulted in the erection of three distinct film producing institutions, namely the Government Film Unit (GFU), the Tanzania Film Company (TFC), and the Audio Visual Institute (AVI). While the GFU was supported by Yugoslavia, the AVI was built with the help of DANIDA. As a socialist leaning non-aligned country, Tanzania sought for support for equipment and knowhow on both sides of the iron curtain. International co-operations in the audiovisual sector raised questions on the degree of self-reliance and autonomy Tanzania could achieve, in the face of economic dependence on equipment and foreign exchange. Another controversial question lay in whether it was more favorable for an independent national film culture to have Tanzanian filmmakers trained abroad individually, or collectively by expatriate instructors within the country. As a frontline state, Tanzania was also eager to create film alliances with neighboring African countries.

Tanzanian film makers tried to overcome the restricting confines of film genres and institutional limitations and saw themselves as critical commentators on society. Throughout the decades, they explored and combined various documentary and fictional formats, inspired by a variety of local and global influences. Global cinema and popular culture found their way in, as much as aesthetics and narratives from traditional Tanzanian art forms such as theatre, literature, and music, generating a genuine Tanzanian style of film making. Retrospectively, a shift can be observed in Tanzanian fiction film from a more classical socialist realism in the 1970s, to what can be called utopian realism in the 1980s, and a notion of magical realism in the 1990s.

The study ends with the decay of state film institutions in the 1990s, while giving an outlook on new phenomena on Tanzania’s audiovisual landscape, namely the introduction of television, the creation of the Zanzibar International Film Festival and the emerging of a local video film industry, the so called ‘Bongo Movies.’

The work, which follows the approach of a historically contextualized film analysis is based on newly digitalized film material that could be restored in cooperation with the Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation throughout my research. In addition, it consults sources from archives in Tanzania, Denmark, Great Britain, and Kenya, as well as newspaper cuttings, autobiographic publications, and interviews conducted with former film makers and cultural decision makers.

Aylin Basaran is a PhD candidate at the Department of Contemporary History, University of Vienna (Chair for Visual and Cultural History), where she has been working as a university assistant and research assistant and is currently affiliated as a research fellow. She is also a lecturer at the Department of Theatre, Film and Media Studies and the Department of Development Studies. Her research focuses are, among others, global film and media history, postcolonial and post-socialist studies, post conflict cinema, memory and trauma studies. She has conducted research in various countries such as Tanzania, Rwanda, South Africa, Kenya, Denmark, Great Britain and the US. In 2017/2018 she was a visiting scholar at the Centre for Film & Media Studies at the University of Cape Town and at the Department of History and the African Studies Center at Michigan State University. She has presented her work on several international conferences, published articles in international journals and books and has co-edited volumes on political strategies in German documentary film, and on sexuality and resistance in international film cultures.